Deborah’s eyes, filled with both warmth and determination, tell a story of triumph over adversity. The lines etched on her face bear witness to a lifetime of experiences, each contributing to the tapestry of her identity. From growing up as a Black lesbian girl in a segregated society to witnessing the civil war as a photographer in Angola in 1989, her regal posture emanates a quiet confidence, a testament to the power she owns.

The photographs captures the essence of a Black, American, lesbian elder who found her home in Berlin since 1999. As a member of the Black feminist collective ADEFRA, inspired by the trailblazing spirit of Caribbean-American feminist poet Audre Lorde, Deborah stands at the intersection of multiple identities and movements.

To me she is an a role model, an elder I admire and who I look up to. The choice of monochrome adds to hera timeless quality, emphasizing the enduring impact of her presence.

Deborah Moses Sanks was born 1949 in Washington D.C. She is a Black american, lesbian photographer who lives in Berlin since 1999 and became part of ADEFRA – formerly known as „AfroDEutsche FRAuen“ (afro-german women) also known as „Schwarze Deutsche Frauen und Schwarze Frauen in Deutschland“ (Black german women and Black women in Germany). Deborah is one of the elders I look up to as a human being, a photographer and as a female identifying person of Black american decent. She allowed me to take her portraits and I had the privilege to learn more about her story as we met at the studio.

When Deborah was a child, her Grandmother was one of countless Black women working for white folks as a domestic help. You can tell by the fact that she had a key to leave and enter their house through the back door but she didn’t have a right to vote, what the political situation meant for a Black women’s live in the United States of America.

Today, being aware of her own family history, the political struggles and changes they went through enables Deborah to see the bigger picture and her role in it. She told me that she will always make sure that her own daughter and grandchildren take advantage of the rights that others had to fight for.

Deborah’s father served as a Black soldier in a segregated military. He would have been citizen enough to give his life for the United States of America but he wasn’t citizen enough to get a regular job as a Black man in a segregated nation until things changed. The family had to move to New York cause the city offered positions at the post office for Black people too. So Deborah’s family moved up north and she grew up in the inner city projects of Brooklyn.

In middle school she took a class in photography and during her first assessment, processing her first pictures and seeing her work coming to light, she realise that this was exactly what she wanted to do to express herself.

She got her first camera, a Minolta, in the 80’s. As a Black lesbian political documentary photographer she went to public events and protests. She witnessed the local Anti-Apartheid Movement, meetings of the Black Panthers and let her pictures shine a light on the daily lives of people who the government turned their back on.

She started to document the homeless in Newark New Jersey for a project of “The Lighthouse” run by Rev. Joan Parrott which was a community center that feed and provided shelter for the homeless. She traveled to Washington D.C, New York City and Philadelphia. As a freelance photogrpher documented the effects of cuts in social welfare – especially on women who could not afford to pay rent anymore.

At the same time she worked as a substitute teacher in Morton Street Elementary School in Newark New Jersey and in Orange New Jersey. She taught reguarly classes just as other permenant terachers: English, Math, social studies, history. There was a little boy in her class. James was about 7 years old and lived in a car with his mother. He could barely hold a pen right. Deborah remembered the first time he wrote his own name, she had tears in her eyes.

The things she saw during that time and the knowledge she gained doing her research on the causes of this suffering she encountered, put her focus even more on the experiences of women and children in the struggle.

Deborah’s daughter served in the military and was stationed in the UK when she had her first grandchild. When Deborah came to visit her and her grandchild someone told her that the military was looking for photographers in Hanau, Germany to take pictures of army equipment for marketing. Eventually Deborah applied for the job, went to an interview and got hired. What a paradox! Since this job enabled her to finance traveling to other countries like Angola and Nicaragua.

“I went to Puerto Cabazas, Nicaragua around 1985/86 and stayed for 3 months with the Chow family in their home for 200 dollars a month – which was nothing considering the exchange rate at the time. Fanny Chow and I became good friends. She prepared 3 meals a day for me, we spent hours talking and going around to the market together”, she says.

I was born in 1985 and by the time I was about four, that year the Berlin wall came down, Deborah went to communist Angola.

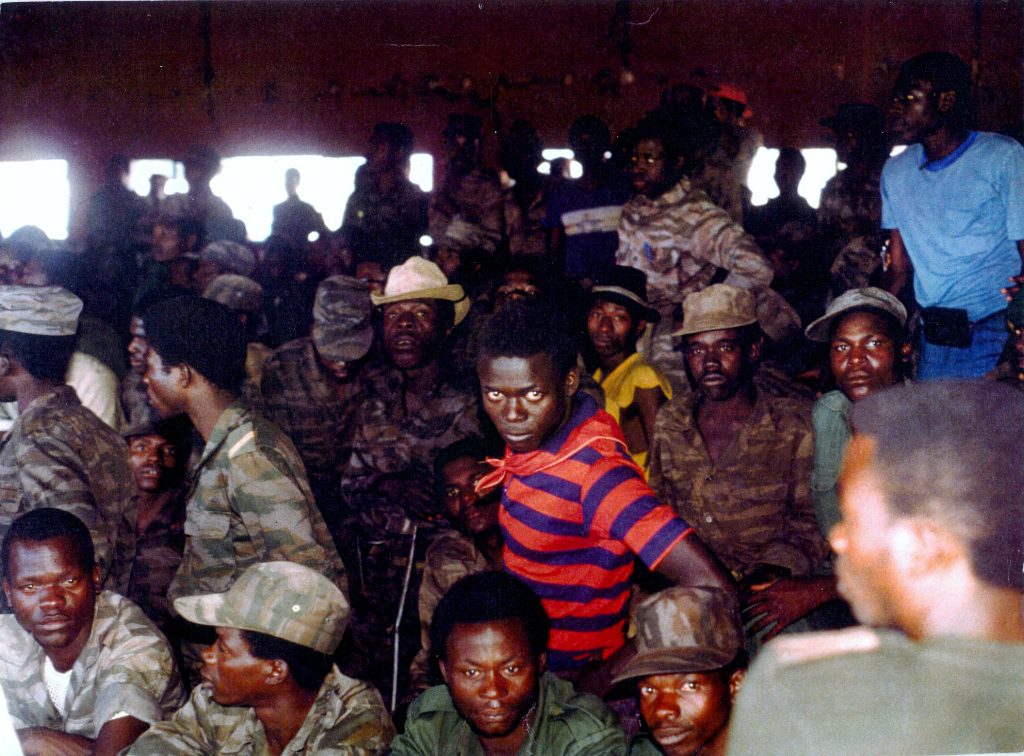

“I was in Angola in 1989. I started out in Luanda and than on to neighboring villages by plane visiting refuge camps and hospitals. I was there for about a week”, she says.

To give some context: During the civil war in Angola the US Government sold land mines to conflicting parties.

In his article for the New York Times, journalist Norimitsu Onishi describes it like this:

„Immediately after gaining independence from Portugal in 1975, Angola slipped into a brutal civil war pitting two former liberation movements (MPLA vs. UNITA). The civil war then became one of the most heated Cold War conflicts on the continent. The Angolans and their respective allies clashed in Cuito Cuanavale in the late 1980s in one of the last century’s biggest battles in Africa. Nowhere are there more mines than here in Cuito Cuanavale, a city in southeastern Angola that was one of the last great battlefields of the Cold War. As the United States and the Soviet Union faced off globally, their proxies laid tens of thousands of mines in Cuito Cuanavale, in an area of Angola then considered so remote and impoverished that it was known as the Land at the End of the World.”

“Angola has more different mine varieties than most mine-affected countries,” said Gerhard Zank, the country manager of the Halo Trust, a private British organization that clears land mines in Angola and other countries.

According to Norimitsu Onishi’s Article “Over the years, the organization’s deminers have found mines from at least 22 countries in Angola, including the former Soviet Union and East Germany”.

In a country where the majority of people works in agriculture countless civilians were killed or havily injuried by land mines during and after war.

Deborah went to Angola with her camera. She saw what the war and the land mines did to this country and remembered it on film 🎞 She told me about dead bodies piled up left and right on the way to an hospital that was already overwhelmed with incoming patients.

She said she will never forget a women sitting on the side of the street. This woman had lost both of her legs and as Deborah was about to take her picture, she turned away from the camera so that Deborah could see she carried her child on her back. Deborah took the picture and it was etched on her memory since.

I‘m taking Deborah‘s story with me, when I will go to Angola. I‘m taking her advice with me, not to use my camera for at least the first 3 weeks, as I enter another place, another society, another part of history. I am more than grateful for this gift and honored to been able to hear what she had to share. Thank you.